Just another heart warming story from the front line...

She was 16 and unexpectedly pregnant. She had been randomly assigned to me by our Maternal Support Services nurse and I had never met her or her family before. During those first few visits with me, she was an emotional pancake, completely flat. Silent except for the most basic responses.

Have you felt the baby move yet?

"Yes."

Are you having any more morning sickness?

"No."

Adopting my best sensitive doctor bedside manner, I would gently but repeatedly try to get inside her head, but she would give up nothing.

How are you feeling about the pregnancy?

"Fine."

Are you anxious about it?

"No."

Is your family supporting you?

"Yeah, I guess."

Is there anything else you want to talk about?

"No."

I would later discover that she, her mother, and her younger brother became patients of our clinic after her alcoholic abusive father had finally driven their car through the front room of their house and they had fled to a nearby domestic violence shelter. One of our outreach nurses had identified them as a high risk family and had them establish care with us. Now that she was pregnant, she would have to leave the shelter and the support of her mother to find a new place to live. That new place turned out to be the home of her baby's father, someone she hardly knew.

I was really concerned about this woman's affect and had talked several times with our MSS nurse about what might happen with this new mother and child. I continued to see her and she remained unengaged and withdrawn until her 20 week ultrasound. The day of the test, I got a call from the ultrasound technologist; she was pretty sure this baby had a cleft lip, maybe worse and we should probably do a more detailed evaluation. "Do you want us to tell the patient?" She asked. Concerned that I hadn't been able to read my patient's emotional state for the entire first half of the pregnancy , I told them to send her back to my office.

Have you felt the baby move yet?

"Yes."

Are you having any more morning sickness?

"No."

Adopting my best sensitive doctor bedside manner, I would gently but repeatedly try to get inside her head, but she would give up nothing.

How are you feeling about the pregnancy?

"Fine."

Are you anxious about it?

"No."

Is your family supporting you?

"Yeah, I guess."

Is there anything else you want to talk about?

"No."

I would later discover that she, her mother, and her younger brother became patients of our clinic after her alcoholic abusive father had finally driven their car through the front room of their house and they had fled to a nearby domestic violence shelter. One of our outreach nurses had identified them as a high risk family and had them establish care with us. Now that she was pregnant, she would have to leave the shelter and the support of her mother to find a new place to live. That new place turned out to be the home of her baby's father, someone she hardly knew.

I was really concerned about this woman's affect and had talked several times with our MSS nurse about what might happen with this new mother and child. I continued to see her and she remained unengaged and withdrawn until her 20 week ultrasound. The day of the test, I got a call from the ultrasound technologist; she was pretty sure this baby had a cleft lip, maybe worse and we should probably do a more detailed evaluation. "Do you want us to tell the patient?" She asked. Concerned that I hadn't been able to read my patient's emotional state for the entire first half of the pregnancy , I told them to send her back to my office.

In my job, you have to be comfortable breaking bad news, but there are times when it is especially difficult. When a patient isn't able to understand the medical issues, for example. Or when someone doesn't have the social support to handle the burden they are given. Or when that person has already had to deal with a string of emotional traumas. I braced myself for the perfect storm.

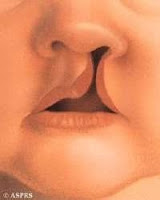

I spent 45 minutes explaining what was going on. Your baby isn't going to look normal. You are going to need a much more detailed evaluation because your baby might have other birth defects. You should see a genetics counselor. Your baby is going to need surgery, probably several, actually. Your baby won't be able to breast feed; yes, if it's really serious there could be a feeding tube, it depends how it goes. I sorry. I know, this is bad news, but we'll be able to deal with it. Don't worry I will be here with you the entire time.

Somehow, and I don't understand from where she summoned it, this sudden news seemed to bring things into sharp focus for her. She came out of her shell. She was emotionally invested in what was going on. Now during her visits, she was the one asking all of the questions. She did everything we asked; she met with the genetics counselor, she went to the Craniofacial surgery clinic, she learned all about feeding a child with a facial malformation. She toured the hospital and took birthing classes. She created a place in her life for a special needs child. When I'd walk into the room to see her, she always greeted me with a smile.

Fortunately, this did appear to be an isolated malformation and her pregnancy proceeded without other events. We still couldn't say exactly how serious the cleft was, whether this child would need one or two surgeries or six or seven. But I did know I had a mother who was going to be confidently prepared as much as is possible. When I gave her the same advice I give to all my pregnant patients nearing their due date, it took on a special significance. "I know you're a little nervous about this, but don't worry. When the time comes, you will know instinctively exactly what you need to do."

When she did go into labor, it was midnight, and unfortunately I wasn't on call until the next morning so I didn't get the word until I arrived at the hospital, just after she had delivered. In the hallway I ran into AF, the doc on call, and she was beaming. She had been up all night with my patient and couldn't say enough about how wonderfully she did and what a beautiful family they made. "It's like pierced Madonna and Child," referring to my patient's multiple facial piercings. "When I told her you'd be here in an hour, her face lit up."

I walked into the room and her face did light up. It is always amazing to see that blissed-out look of love in a mother's eyes as she holds her new baby but to see it in this woman's eyes was honestly a career highlight, a rare reward for years of slogging it out in the urban underserved primary care trenches where most stories seem to end badly. If there was anything wrong with this baby, you would never know it looking at his mother.

As she handed the baby to me, I could see that his cleft was actually pretty serious, probably the worst case scenario, involving the entire palate and extending through the nose. He's going to need several surgeries over several years. Now the work really begins. First order of business: figure out how to feed the baby.

Mom listened closely as we brought in lactation consultants and speech therapists during those first days in the hospital. She became increasingly confident with the special bottles and nipples we gave her and she firmly committed to giving her baby only breast milk, even if it meant having to pump all of it and gently using the special squeeze bottles that worked with her baby.

The baby is now one week old. Mom is still completely in love and the baby has nearly regained his birth weight. He looks great.

A lot of times, you look back in awe at the history you have with certain patients, honored to share in those intimate moments of crisis. You witness them take terrible, overwhelming news and summon all their stregnth to try and create something positive. It's the most basic human struggle and it's the reason why I chose medicine. The situation with this baby is unique in that I'm able to look ahead; this kid is going to go through a lot of medical care over the years, and I'll get to be a part of it. I choose to believe he's going to have a great life and I have the privledge and responsibility to do what I can to make that a reality.

Comments